Bears are carnivoran mammals of the family Ursidae (/ˈɜːrsɪdiː, -daɪ/). They are classified as caniforms, or doglike carnivorans. Although only eight species of bears are extant, they are widespread, appearing in a wide variety of habitats throughout most of the Northern Hemisphere and partially in the Southern Hemisphere. Bears are found on the continents of North America, South America, and Eurasia. Common characteristics of modern bears include large bodies with stocky legs, long snouts, small rounded ears, shaggy hair, plantigrade paws with five nonretractile claws, and short tails.

While the polar bear is mostly carnivorous, and the giant panda is mostly herbivorous, the remaining six species are omnivorous with varying diets. With the exception of courting individuals and mothers with their young, bears are typically solitary animals. They may be diurnal or nocturnal and have an excellent sense of smell. Despite their heavy build and awkward gait, they are adept runners, climbers, and swimmers. Bears use shelters, such as caves and logs, as their dens; most species occupy their dens during the winter for a long period of hibernation, up to 100 days.

Bears have been hunted since prehistoric times for their meat and fur; they have also been used for bear-baiting and other forms of entertainment, such as being made to dance. With their powerful physical presence, they play a prominent role in the arts, mythology, and other cultural aspects of various human societies. In modern times, bears have come under pressure through encroachment on their habitats and illegal trade in bear parts, including the Asian bile bear market. The IUCN lists six bear species as vulnerable or endangered, and even least concern species, such as the brown bear, are at risk of extirpation in certain countries. The poaching and international trade of these most threatened populations are prohibited, but still ongoing.

Etymology

The English word “bear” comes from Old English bera and belongs to a family of names for the bear in Germanic languages, such as Swedish björn, also used as a first name. This form is conventionally said to be related to a Proto-Indo-European word for “brown”, so that “bear” would mean “the brown one”.[1][2] However, Ringe notes that while this etymology is semantically plausible, a word meaning “brown” of this form cannot be found in Proto-Indo-European. He suggests instead that “bear” is from the Proto-Indo-European word *ǵʰwḗr- ~ *ǵʰwér “wild animal”.[3] This terminology for the animal originated as a taboo avoidance term: proto-Germanic tribes replaced their original word for bear—arkto—with this euphemistic expression out of fear that speaking the animal’s true name might cause it to appear.[4][5] According to author Ralph Keyes, this is the oldest known euphemism.[6]

Bear taxon names such as Arctoidea and Helarctos come from the ancient Greek ἄρκτος (arktos), meaning bear,[7] as do the names “arctic” and “antarctic“, via the name of the constellation Ursa Major, the “Great Bear”, prominent in the northern sky.[8]

Bear taxon names such as Ursidae and Ursus come from Latin Ursus/Ursa, he-bear/she-bear.[8] The female first name “Ursula“, originally derived from a Christian saint‘s name, means “little she-bear” (diminutive of Latin ursa). In Switzerland, the male first name “Urs” is especially popular, while the name of the canton and city of Bern is by legend derived from Bär, German for bear. The Germanic name Bernard (including Bernhardt and similar forms) means “bear-brave”, “bear-hardy”, or “bold bear”.[9][10] The Old English name Beowulf is a kenning, “bee-wolf”, for bear, in turn meaning a brave warrior.[11]

Taxonomy

Further information: List of ursids

The family Ursidae is one of nine families in the suborder Caniformia, or “doglike” carnivorans, within the order Carnivora. Bears’ closest living relatives are the pinnipeds, canids, and musteloids.[12] (Some scholars formerly argued that bears are directly derived from canids and should not be classified as a separate family.)[13] Modern bears comprise eight species in three subfamilies: Ailuropodinae (monotypic with the giant panda), Tremarctinae (monotypic with the spectacled bear), and Ursinae (containing six species divided into one to three genera, depending on the authority). Nuclear chromosome analysis show that the karyotype of the six ursine bears is nearly identical, each having 74 chromosomes (see Ursid hybrid), whereas the giant panda has 42 chromosomes and the spectacled bear 52. These smaller numbers can be explained by the fusing of some chromosomes, and the banding patterns on these match those of the ursine species, but differ from those of procyonids, which supports the inclusion of these two species in Ursidae rather than in Procyonidae, where they had been placed by some earlier authorities.[14]

Evolution

The earliest members of Ursidae belong to the extinct subfamily Amphicynodontinae, including Parictis (late Eocene to early middle Miocene, 38–18 Mya) and the slightly younger Allocyon (early Oligocene, 34–30 Mya), both from North America. These animals looked very different from today’s bears, being small and raccoon-like in overall appearance, with diets perhaps more similar to that of a badger. Parictis does not appear in Eurasia and Africa until the Miocene.[15] It is unclear whether late-Eocene ursids were also present in Eurasia, although faunal exchange across the Bering land bridge may have been possible during a major sea level low stand as early as the late Eocene (about 37 Mya) and continuing into the early Oligocene.[16] European genera morphologically very similar to Allocyon, and to the much younger American Kolponomos (about 18 Mya),[17] are known from the Oligocene, including Amphicticeps and Amphicynodon.[16] There has been various morphological evidence linking amphicynodontines with pinnipeds, as both groups were semi-aquatic, otter-like mammals.[18][19][20] In addition to the support of the pinniped–amphicynodontine clade, other morphological and some molecular evidence supports bears being the closest living relatives to pinnipeds.[21][22][23][19][24][20]

The raccoon-sized, dog-like Cephalogale is the oldest-known member of the subfamily Hemicyoninae, which first appeared during the middle Oligocene in Eurasia about 30 Mya.[16] The subfamily includes the younger genera Phoberocyon (20–15 Mya), and Plithocyon (15–7 Mya). A Cephalogale-like species gave rise to the genus Ursavus during the early Oligocene (30–28 Mya); this genus proliferated into many species in Asia and is ancestral to all living bears. Species of Ursavus subsequently entered North America, together with Amphicynodon and Cephalogale, during the early Miocene (21–18 Mya). Members of the living lineages of bears diverged from Ursavus between 15 and 20 Mya,[25][26] likely via the species Ursavus elmensis. Based on genetic and morphological data, the Ailuropodinae (pandas) were the first to diverge from other living bears about 19 Mya, although no fossils of this group have been found before about 11 Mya.[27][28]

The New World short-faced bears (Tremarctinae) differentiated from Ursinae following a dispersal event into North America during the mid-Miocene (about 13 Mya).[27] They invaded South America (≈2.5 or 1.2 Ma) following formation of the Isthmus of Panama.[29] Their earliest fossil representative is Plionarctos in North America (c. 10–2 Ma). This genus is probably the direct ancestor to the North American short-faced bears (genus Arctodus), the South American short-faced bears (Arctotherium), and the spectacled bears, Tremarctos, represented by both an extinct North American species (T. floridanus), and the lone surviving representative of the Tremarctinae, the South American spectacled bear (T. ornatus).[16]

The subfamily Ursinae experienced a dramatic proliferation of taxa about 5.3–4.5 Mya, coincident with major environmental changes; the first members of the genus Ursus appeared around this time. The sloth bear is a modern survivor of one of the earliest lineages to diverge during this radiation event (5.3 Mya); it took on its peculiar morphology, related to its diet of termites and ants, no later than by the early Pleistocene. By 3–4 Mya, the species Ursus minimus appears in the fossil record of Europe; apart from its size, it was nearly identical to today’s Asian black bear. It is likely ancestral to all bears within Ursinae, perhaps aside from the sloth bear. Two lineages evolved from U. minimus: the black bears (including the sun bear, the Asian black bear, and the American black bear); and the brown bears (which includes the polar bear). Modern brown bears evolved from U. minimus via Ursus etruscus, which itself is ancestral to the extinct Pleistocene cave bear.[27] Species of Ursinae have migrated repeatedly into North America from Eurasia as early as 4 Mya during the early Pliocene.[30][31] The polar bear is the most recently evolved species and descended from a population of brown bears that became isolated in northern latitudes by glaciation 400,000 years ago.[32]

Phylogeny

The relationship of the bear family with other carnivorans is shown in the following phylogenetic tree, which is based on the molecular phylogenetic analysis of six genes in Flynn (2005)[33] with the musteloids updated following the multigene analysis of Law et al. (2018).[34]

| Carnivora | Feliformia CaniformiaCanidae ArctoideaUrsidae Pinnipedia MusteloideaMephitidae Ailuridae Procyonidae Mustelidae |

Note that although they are called “bears” in some languages, red pandas and raccoons and their close relatives are not bears, but rather musteloids.[33]

There are two phylogenetic hypotheses on the relationships among extant and fossil bear species. One is all species of bears are classified in seven subfamilies as adopted here and related articles: Amphicynodontinae, Hemicyoninae, Ursavinae, Agriotheriinae, Ailuropodinae, Tremarctinae, and Ursinae.[13][35][36][37] Below is a cladogram of the subfamilies of bears after McLellan and Reiner (1992)[13] and Qiu et al.. (2014):[37][clarification needed]

The second alternative phylogenetic hypothesis was implemented by McKenna et al. (1997) to classify all the bear species into the superfamily Ursoidea, with Hemicyoninae and Agriotheriinae being classified in the family “Hemicyonidae”.[38] Amphicynodontinae under this classification were classified as stem-pinnipeds in the superfamily Phocoidea.[38] In the McKenna and Bell classification, both bears and pinnipeds are in a parvorder of carnivoran mammals known as Ursida, along with the extinct bear dogs of the family Amphicyonidae.[38] Below is the cladogram based on McKenna and Bell (1997) classification:[38][clarification needed]

| Ursida | †Amphicyonidae Phocoidea†Amphicynodontidae Pinnipedia Ursoidea†Hemicyonidae†Hemicyoninae†AgriotheriinaeUrsidae†UrsavinaeAiluropodinae Tremarctinae Ursinae |

| A possible phylogeny based on complete mitochondrial DNA sequences from Yu et al. (2007).[39] |

|---|

| UrsidaeGiant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) Spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus) UrsinaeSloth bear (Melursus ursinus) Sun bear (Helarctos malayanus) Asian black bear (Ursus thibetanus) American black bear (Ursus americanus) Polar bear (Ursus maritimus) Brown bear (Ursus arctos) |

| The polar bear and the brown bear form a close grouping, while the relationships of the other species are not very well resolved.[14] |

| A more recent phylogeny based on the genetic study of Kumar et al. (2017).[40] |

|---|

| UrsidaeGiant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) Spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus) UrsinaeSloth bear (Melursus ursinus) Sun bear (Helarctos malayanus) Asian black bear (Ursus thibetanus) American black bear (Ursus americanus) Polar bear (Ursus maritimus) Brown bear (Ursus arctos) |

| The study concludes that Ursine bears originated around five million years ago and show extensive hybridization of species in their lineage.[40] |

Physical characteristics

Size

Polar bear (left) and sun bear, the largest and smallest species respectively, on average

The bear family includes the most massive extant terrestrial members of the order Carnivora.[a] The polar bear is considered to be the largest extant species,[42] with adult males weighing 350–700 kg (770–1,540 lb) and measuring 2.4–3 m (7 ft 10 in – 9 ft 10 in) in total length.[43] The smallest species is the sun bear, which ranges 25–65 kg (55–143 lb) in weight and 100–140 cm (39–55 in) in length.[44] Prehistoric North and South American short-faced bears were the largest species known to have lived. The latter estimated to have weighed 1,600 kg (3,500 lb) and stood 3.4 m (11 ft) tall.[45][46] Body weight varies throughout the year in bears of temperate and arctic climates, as they build up fat reserves in the summer and autumn and lose weight during the winter.[47]

Morphology

Bears are generally bulky and robust animals with short tails. They are sexually dimorphic with regard to size, with males typically being larger.[48][49] Larger species tend to show increased levels of sexual dimorphism in comparison to smaller species.[49] Relying as they do on strength rather than speed, bears have relatively short limbs with thick bones to support their bulk. The shoulder blades and the pelvis are correspondingly massive. The limbs are much straighter than those of the big cats as there is no need for them to flex in the same way due to the differences in their gait. The strong forelimbs are used to catch prey, excavate dens, dig out burrowing animals, turn over rocks and logs to locate prey, and club large creatures.[47]

Unlike most other land carnivorans, bears are plantigrade. They distribute their weight toward the hind feet, which makes them look lumbering when they walk. They are capable of bursts of speed but soon tire, and as a result mostly rely on ambush rather than the chase. Bears can stand on their hind feet and sit up straight with remarkable balance. Their front paws are flexible enough to grasp fruit and leaves. Bears’ non-retractable claws are used for digging, climbing, tearing, and catching prey. The claws on the front feet are larger than those on the back and may be a hindrance when climbing trees; black bears are the most arboreal of the bears, and have the shortest claws. Pandas are unique in having a bony extension on the wrist of the front feet which acts as a thumb, and is used for gripping bamboo shoots as the animals feed.[47]

Most mammals have agouti hair, with each individual hair shaft having bands of color corresponding to two different types of melanin pigment. Bears however have a single type of melanin and the hairs have a single color throughout their length, apart from the tip which is sometimes a different shade. The coat consists of long guard hairs, which form a protective shaggy covering, and short dense hairs which form an insulating layer trapping air close to the skin. The shaggy coat helps maintain body heat during winter hibernation and is shed in the spring leaving a shorter summer coat. Polar bears have hollow, translucent guard hairs which gain heat from the sun and conduct it to the dark-colored skin below. They have a thick layer of blubber for extra insulation, and the soles of their feet have a dense pad of fur.[47] While bears tend to be uniform in color, some species may have markings on the chest or face and the giant panda has a bold black-and-white pelage.[50]

Bears have small rounded ears so as to minimize heat loss, but neither their hearing or sight are particularly acute. Unlike many other carnivorans they have color vision, perhaps to help them distinguish ripe nuts and fruits. They are unique among carnivorans in not having touch-sensitive whiskers on the muzzle; however, they have an excellent sense of smell, better than that of the dog, or possibly any other mammal. They use smell for signalling to each other (either to warn off rivals or detect mates) and for finding food. Smell is the principal sense used by bears to locate most of their food, and they have excellent memories which helps them to relocate places where they have found food before.[47]

The skulls of bears are massive, providing anchorage for the powerful masseter and temporal jaw muscles. The canine teeth are large but mostly used for display, and the molar teeth flat and crushing. Unlike most other members of the Carnivora, bears have relatively undeveloped carnassial teeth, and their teeth are adapted for a diet that includes a significant amount of vegetable matter.[47] Considerable variation occurs in dental formula even within a given species. This may indicate bears are still in the process of evolving from a mainly meat-eating diet to a predominantly herbivorous one. Polar bears appear to have secondarily re-evolved carnassial-like cheek teeth, as their diets have switched back towards carnivory.[51] Sloth bears lack lower central incisors and use their protrusible lips for sucking up the termites on which they feed.[47] The general dental formula for living bears is: 3.1.2–4.23.1.2–4.3.[47] The structure of the larynx of bears appears to be the most basal of the caniforms.[52] They possess air pouches connected to the pharynx which may amplify their vocalizations.[53]

Bears have a fairly simple digestive system typical for carnivorans, with a single stomach, short undifferentiated intestines and no cecum.[54][55] Even the herbivorous giant panda still has the digestive system of a carnivore, as well as carnivore-specific genes. Its ability to digest cellulose is ascribed to the microbes in its gut.[56] Bears must spend much of their time feeding in order to gain enough nutrition from foliage. The panda, in particular, spends 12–15 hours a day feeding.[57]

Distribution and habitat

Further information: List of carnivorans by population

Extant bears are found in sixty countries primarily in the Northern Hemisphere and are concentrated in Asia, North America, and Europe. An exception is the spectacled bear; native to South America, it inhabits the Andean region.[58] The sun bear‘s range extends below the equator in Southeast Asia.[59] The Atlas bear, a subspecies of the brown bear was distributed in North Africa from Morocco to Libya, but it became extinct around the 1870s.[60]

The most widespread species is the brown bear, which occurs from Western Europe eastwards through Asia to the western areas of North America. The American black bear is restricted to North America, and the polar bear is restricted to the Arctic Ocean. All the remaining species of bear are Asian.[58] They occur in a range of habitats which include tropical lowland rainforest, both coniferous and broadleaf forests, prairies, steppes, montane grassland, alpine scree slopes, Arctic tundra and in the case of the polar bear, ice floes.[58][61] Bears may dig their dens in hillsides or use caves, hollow logs and dense vegetation for shelter.[61]

Behavior and ecology

Brown and American black bears are generally diurnal, meaning that they are active for the most part during the day, though they may forage substantially by night.[62] Other species may be nocturnal, active at night, though female sloth bears with cubs may feed more at daytime to avoid competition from conspecifics and nocturnal predators.[63] Bears are overwhelmingly solitary and are considered to be the most asocial of all the Carnivora. The only times bears are encountered in groups are mothers with young or occasional seasonal bounties of rich food (such as salmon runs).[64][65] Fights between males can occur and older individuals may have extensive scarring, which suggests that maintaining dominance can be intense.[66] With their acute sense of smell, bears can locate carcasses from several kilometres away. They use olfaction to locate other foods, encounter mates, avoid rivals and recognize their cubs.[47]

Feeding

Most bears are opportunistic omnivores and consume more plant than animal matter, and appear to have evolved from an ancestor which was a low-protein macronutrient omnivore.[67] They eat anything from leaves, roots, and berries to insects, carrion, fresh meat, and fish, and have digestive systems and teeth adapted to such a diet.[58] At the extremes are the almost entirely herbivorous giant panda and the mostly carnivorous polar bear. However, all bears feed on any food source that becomes seasonally available.[57] For example, Asiatic black bears in Taiwan consume large numbers of acorns when these are most common, and switch to ungulates at other times of the year.[68]

When foraging for plants, bears choose to eat them at the stage when they are at their most nutritious and digestible, typically avoiding older grasses, sedges and leaves.[55][57] Hence, in more northern temperate areas, browsing and grazing is more common early in spring and later becomes more restricted.[69] Knowing when plants are ripe for eating is a learned behavior.[57] Berries may be foraged in bushes or at the tops of trees, and bears try to maximize the number of berries consumed versus foliage.[69] In autumn, some bear species forage large amounts of naturally fermented fruits, which affects their behavior.[70] Smaller bears climb trees to obtain mast (edible reproductive parts, such as acorns).[71] Such masts can be very important to the diets of these species, and mast failures may result in long-range movements by bears looking for alternative food sources.[72] Brown bears, with their powerful digging abilities, commonly eat roots.[69] The panda’s diet is over 99% bamboo,[73] of 30 different species. Its strong jaws are adapted for crushing the tough stems of these plants, though they prefer to eat the more nutritious leaves.[74][75] Bromeliads can make up to 50% of the diet of the spectacled bear, which also has strong jaws to bite them open.[76]

The sloth bear is not as specialized as polar bears and the panda, has lost several front teeth usually seen in bears, and developed a long, suctioning tongue to feed on the ants, termites, and other burrowing insects. At certain times of the year, these insects can make up 90% of their diets.[77] Some individuals become addicted to sweets in garbage inside towns where tourism-related waste is generated throughout the year.[78] Some species may raid the nests of wasps and bees for the honey and immature insects, in spite of stinging from the adults.[79] Sun bears use their long tongues to lick up both insects and honey.[80] Fish are an important source of food for some species, and brown bears in particular gather in large numbers at salmon runs. Typically, a bear plunges into the water and seizes a fish with its jaws or front paws. The preferred parts to eat are the brain and eggs. Small burrowing mammals like rodents may be dug out and eaten.[81][69]

The brown bear and both species of black bears sometimes take large ungulates, such as deer and bovids, mostly the young and weak.[68][82][81] These animals may be taken by a short rush and ambush, though hiding young may be sniffed out and pounced on.[69][83] The polar bear mainly preys on seals, stalking them from the ice or breaking into their dens. They primarily eat the highly digestible blubber.[84][81] Large mammalian prey is typically killed with raw strength, including bites and paw swipes, and bears do not display the specialized killing methods of felids and canids.[85] Predatory behavior in bears is typically taught to the young by the mother.[81]

Bears are prolific scavengers and kleptoparasites, stealing food caches from rodents, and carcasses from other predators.[55][86] For hibernating species, weight gain is important as it provides nourishment during winter dormancy. A brown bear can eat 41 kg (90 lb) of food and gain 2–3 kg (4.4–6.6 lb) of fat a day prior to entering its den.[87]

Communication

Bears produce a number of vocal and non-vocal sounds. Tongue-clicking, grunting or chuffing many be made in cordial situations, such as between mothers and cubs or courting couples, while moaning, huffing, snorting or blowing air is made when an individual is stressed. Barking is produced during times of alarm, excitement or to give away the animal’s position. Warning sounds include jaw-clicking and lip-popping, while teeth-chatters, bellows, growls, roars and pulsing sounds are made in aggressive encounters. Cubs may squeal, bawl, bleat or scream when in distress and make motor-like humming when comfortable or nursing.[52][88][89][90][91][92]

Bears sometimes communicate with visual displays such as standing upright, which exaggerates the individual’s size. The chest markings of some species may add to this intimidating display. Staring is an aggressive act and the facial markings of spectacled bears and giant pandas may help draw attention to the eyes during agonistic encounters.[50] Individuals may approach each other by stiff-legged walking with the head lowered. Dominance between bears is asserted by making a frontal orientation, showing the canine teeth, muzzle twisting and neck stretching. A subordinate may respond with a lateral orientation, by turning away and dropping the head and by sitting or lying down.[65][93]

Bears also communicate with their scent by urinating on[94] or rubbing against trees and other objects.[95] This is usually accompanied by clawing and biting the object. Bark may be spread around to draw attention to the marking post.[96] Pandas establish territories by marking objects with urine and a waxy substance from their anal glands.[97] Polar bears leave behind their scent in their tracks which allow individuals to keep track of one another in the vast Arctic wilderness.[98]

Reproduction and development

The mating system of bears has variously been described as a form of polygyny, promiscuity and serial monogamy.[99][100][101] During the breeding season, males take notice of females in their vicinity and females become more tolerant of males. A male bear may visit a female continuously over a period of several days or weeks, depending on the species, to test her reproductive state. During this time period, males try to prevent rivals from interacting with their mate. Courtship may be brief, although in some Asian species, courting pairs may engage in wrestling, hugging, mock fighting and vocalizing. Ovulation is induced by mating, which can last up to 30 minutes depending on the species.[100]Duration: 38 seconds.0:38Polar bear mother nursing her cub

Gestation typically lasts six to nine months, including delayed implantation, and litter size numbers up to four cubs.[102] Giant pandas may give birth to twins but they can only suckle one young and the other is left to die.[103] In northern living species, birth takes place during winter dormancy. Cubs are born blind and helpless with at most a thin layer of hair, relying on their mother for warmth. The milk of the female bear is rich in fat and antibodies and cubs may suckle for up to a year after they are born. By two to three months, cubs can follow their mother outside the den. They usually follow her on foot, but sloth bear cubs may ride on their mother’s back.[102][61] Male bears play no role in raising young. Infanticide, where an adult male kills the cubs of another, has been recorded in polar bears, brown bears and American black bears but not in other species.[104] Males kill young to bring the female into estrus.[105] Cubs may flee and the mother defends them even at the cost of her life.[106][107][108]

In some species, offspring may become independent around the next spring, though some may stay until the female successfully mates again. Bears reach sexual maturity shortly after they disperse; at around three to six years depending on the species. Male Alaskan brown bears and polar bears may continue to grow until they are 11 years old.[102] Lifespan may also vary between species. The brown bear can live an average of 25 years.[109]

Hibernation

Main article: Hibernation

Bears of northern regions, including the American black bear and the grizzly bear, hibernate in the winter.[110][111] During hibernation, the bear’s metabolism slows down, its body temperature decreases slightly, and its heart rate slows from a normal value of 55 to just 9 beats per minute.[112] Bears normally do not wake during their hibernation, and can go the entire period without eating, drinking, urinating, or defecating.[47] A fecal plug is formed in the colon, and is expelled when the bear wakes in the spring.[113] If they have stored enough body fat, their muscles remain in good condition, and their protein maintenance requirements are met from recycling waste urea.[47] Female bears give birth during the hibernation period, and are roused when doing so.[111]

Mortality

Bears do not have many predators. The most important are humans, and as they started cultivating crops, they increasingly came in conflict with the bears that raided them. Since the invention of firearms, people have been able to kill bears with greater ease.[114] Felids like the tiger may also prey on bears,[115][116] particularly cubs, which may also be threatened by canids.[14][101]

Bears are parasitized by eighty species of parasites, including single-celled protozoans and gastro-intestinal worms, and nematodes and flukes in their heart, liver, lungs and bloodstream. Externally, they have ticks, fleas and lice. A study of American black bears found seventeen species of endoparasite including the protozoan Sarcocystis, the parasitic worm Diphyllobothrium mansonoides, and the nematodes Dirofilaria immitis, Capillaria aerophila, Physaloptera sp., Strongyloides sp. and others. Of these, D. mansonoides and adult C. aerophila were causing pathological symptoms.[117] By contrast, polar bears have few parasites; many parasitic species need a secondary, usually terrestrial, host, and the polar bear’s life style is such that few alternative hosts exist in their environment. The protozoan Toxoplasma gondii has been found in polar bears, and the nematode Trichinella nativa can cause a serious infection and decline in older polar bears.[118] Bears in North America are sometimes infected by a Morbillivirus similar to the canine distemper virus.[119] They are susceptible to infectious canine hepatitis (CAV-1), with free-living black bears dying rapidly of encephalitis and hepatitis.[120]

Relationship with humans

Conservation

Main article: Bear conservation

Giant pandas at the Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuaries

A barrel trap in Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming, used to relocate bears away from where they might attack humans.

In modern times, bears have come under pressure through encroachment on their habitats[121] and illegal trade in bear parts, including the Asian bile bear market, though hunting is now banned, largely replaced by farming.[122] The IUCN lists six bear species as vulnerable;[123] even the two least concern species, the brown bear and the American black bear,[123] are at risk of extirpation in certain areas. In general, these two species inhabit remote areas with little interaction with humans, and the main non-natural causes of mortality are hunting, trapping, road-kill and depredation.[124]

Laws have been passed in many areas of the world to protect bears from habitat destruction. Public perception of bears is often positive, as people identify with bears due to their omnivorous diets, their ability to stand on two legs, and their symbolic importance.[125] Support for bear protection is widespread, at least in more affluent societies.[126] The giant panda has become a worldwide symbol of conservation. The Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuaries, which are home to around 30% of the wild panda population, gained a UNESCO World Heritage Site designation in 2006.[127] Where bears raid crops or attack livestock, they may come into conflict with humans.[128][129] In poorer rural regions, attitudes may be more shaped by the dangers posed by bears, and the economic costs they cause to farmers and ranchers.[128]

Attacks

Main article: Bear attack

Several bear species are dangerous to humans, especially in areas where they have become used to people; elsewhere, they generally avoid humans. Injuries caused by bears are rare, but are widely reported.[130] Bears may attack humans in response to being startled, in defense of young or food, or even for predatory reasons.[131]

Entertainment, hunting, food and folk medicine

Bears in captivity have for centuries been used for entertainment. They have been trained to dance,[132] and were kept for baiting in Europe from at least the 16th century. There were five bear-baiting gardens in Southwark, London, at that time; archaeological remains of three of these have survived.[133] Across Europe, nomadic Romani bear handlers called Ursari lived by busking with their bears from the 12th century.[134]

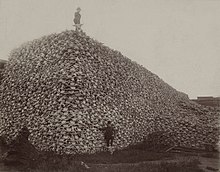

Bears have been hunted for sport, food, and folk medicine. Their meat is dark and stringy, like a tough cut of beef. In Cantonese cuisine, bear paws are considered a delicacy. Bear meat should be cooked thoroughly, as it can be infected with the parasite Trichinella spiralis.[135][136]

The peoples of eastern Asia use bears’ body parts and secretions (notably their gallbladders and bile) as part of traditional Chinese medicine. More than 12,000 bears are thought to be kept on farms in China, Vietnam, and South Korea for the production of bile. Trade in bear products is prohibited under CITES, but bear bile has been detected in shampoos, wine and herbal medicines sold in Canada, the United States and Australia.[137]

- The Dancing Bear by William Frederick Witherington, 1822

- A nomadic ursar, a Romani bear-busker. Drawing by Theodor Aman, 1888

Cultural depictions

Main article: Cultural depictions of bears

See also: Bear in heraldry

Bears have been popular subjects in art, literature, folklore and mythology. The image of the mother bear was prevalent throughout societies in North America and Eurasia, based on the female’s devotion and protection of her cubs.[138] In many Native American cultures, the bear is a symbol of rebirth because of its hibernation and re-emergence.[139] A widespread belief among cultures of North America and northern Asia associated bears with shaman; this may be based on the solitary nature of both. Bears have thus been thought to predict the future and shaman were believed to have been capable of transforming into bears.[140]

There is evidence of prehistoric bear worship, though this is disputed by archaeologists.[141] It is possible that bear worship existed in early Chinese and Ainu cultures.[142] The prehistoric Finns,[143] Siberian peoples[144] and more recently Koreans considered the bear as the spirit of their forefathers.[145] Artio (Dea Artio in the Gallo-Roman religion) was a Celtic bear goddess. Evidence of her worship has notably been found at Bern, itself named for the bear. Her name is derived from the Celtic word for “bear”, artos.[146] In ancient Greece, the archaic cult of Artemis in bear form survived into Classical times at Brauron, where young Athenian girls passed an initiation rite as arktoi “she bears”.[147]

The constellations of Ursa Major and Ursa Minor, the great and little bears, are named for their supposed resemblance to bears, from the time of Ptolemy.[b][8] The nearby star Arcturus means “guardian of the bear”, as if it were watching the two constellations.[149] Ursa Major has been associated with a bear for as much as 13,000 years since Paleolithic times, in the widespread Cosmic Hunt myths. These are found on both sides of the Bering land bridge, which was lost to the sea some 11,000 years ago.[150]

Bears are popular in children’s stories, including Winnie the Pooh,[151] Paddington Bear,[152] Gentle Ben[153] and “The Brown Bear of Norway“.[154] An early version of “Goldilocks and the Three Bears“,[155] was published as “The Three Bears” in 1837 by Robert Southey, many times retold, and illustrated in 1918 by Arthur Rackham.[156] The Hanna-Barbera character Yogi Bear has appeared in numerous comic books, animated television shows and films.[157][158] The Care Bears began as greeting cards in 1982, and were featured as toys, on clothing and in film.[159] Around the world, many children—and some adults—have teddy bears, stuffed toys in the form of bears, named after the American statesman Theodore Roosevelt when in 1902 he had refused to shoot an American black bear tied to a tree.[160]

Bears, like other animals, may symbolize nations. The Russian Bear has been a common national personification for Russia from the 16th century onward.[161] Smokey Bear has become a part of American culture since his introduction in 1944, with his message “Only you can prevent forest fires”.[162]

- “The Three Bears”, Arthur Rackham‘s illustration to English Fairy Tales, by Flora Annie Steel, 1918

- The constellation of Ursa Major as depicted in Urania’s Mirror, c. 1825

Organizations

The International Association for Bear Research & Management, also known as the International Bear Association, and the Bear Specialist Group of the Species Survival Commission, a part of the International Union for Conservation of Nature focus on the natural history, management, and conservation of bears. Bear Trust International works for wild bears and other wildlife through four core program initiatives, namely Conservation Education, Wild Bear Research, Wild Bear Management, and Habitat Conservation.[163]

Specialty organizations for each of the eight species of bears worldwide include:

- Vital Ground, for the brown bear[164]

- Moon Bears, for the Asiatic black bear[165]

- Black Bear Conservation Coalition, for the North American black bear[166]

- Polar Bears International, for the polar bear[167]

- Bornean Sun Bear Conservation Centre, for the sun bear[168]

- Wildlife SOS, for the sloth bear[169]

- Andean Bear Conservation Project, for the Andean bear[170]

- Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding, for the giant panda